With the highest suicide rate and number of deaths by suicide – in fact, more deaths by suicide per year than all of OSHA’s Fatal Four Hazards combined – the construction industry must continue its suicide prevention efforts.

Despite a company’s best efforts to address suicide prevention, learning that an employee, family member, subcontractor, supplier, or professional business partner has experienced a death by suicide is devastating. Part of suicide prevention is to address how to handle the aftermath of a suicide loss, known as suicide postvention.

This article will share perspectives, strategies, resources, and tools to help contractors respond appropriately if the unthinkable should happen.

What Is Suicide Postvention?

The Suicide Prevention Resource Center defines postvention as the provision of crisis intervention and other support after a suicide has occurred to address and alleviate possible effects of suicide. Effective postvention has been found to stabilize the community and facilitate the return to a new normal.

Most important, it can help prevent suicide contagion. Studies have shown that the exposure to suicide or suicidal behaviors within one’s family, one’s peer group, or media reports of suicide can result in an increase in suicide and suicidal behaviors. This contagion effect is especially true among teens and young adults when communication about the death is sensationalized, graphic, or promotes a destructive cause. Sometimes the rationale for this increase in suicide or suicidal behavior occurs out of guilt, a distorted sense of loyalty, or a perceived false “permission” to do so.

Put simply, suicide postvention is the full spectrum of support services made available to survivors in the aftermath of a death by suicide.

Specifically, for a contractor, this can include conducting a formal critical incident debriefing session or an informal safety huddle. This can also include bringing in behavioral specialists representing a labor union or the company’s employee assistance program (EAP).

The purpose of a critical incident debriefing session or safety huddle is to reinforce the company’s commitment to the psychological safety and well-being of its employees, which reflects the company’s caring culture. This serves to humanize the deceased and promotes improved acceptance by coworkers. Acknowledging the death by suicide (rather than ignoring it) is an effective way to reduce the stigma.

Elements of Postvention

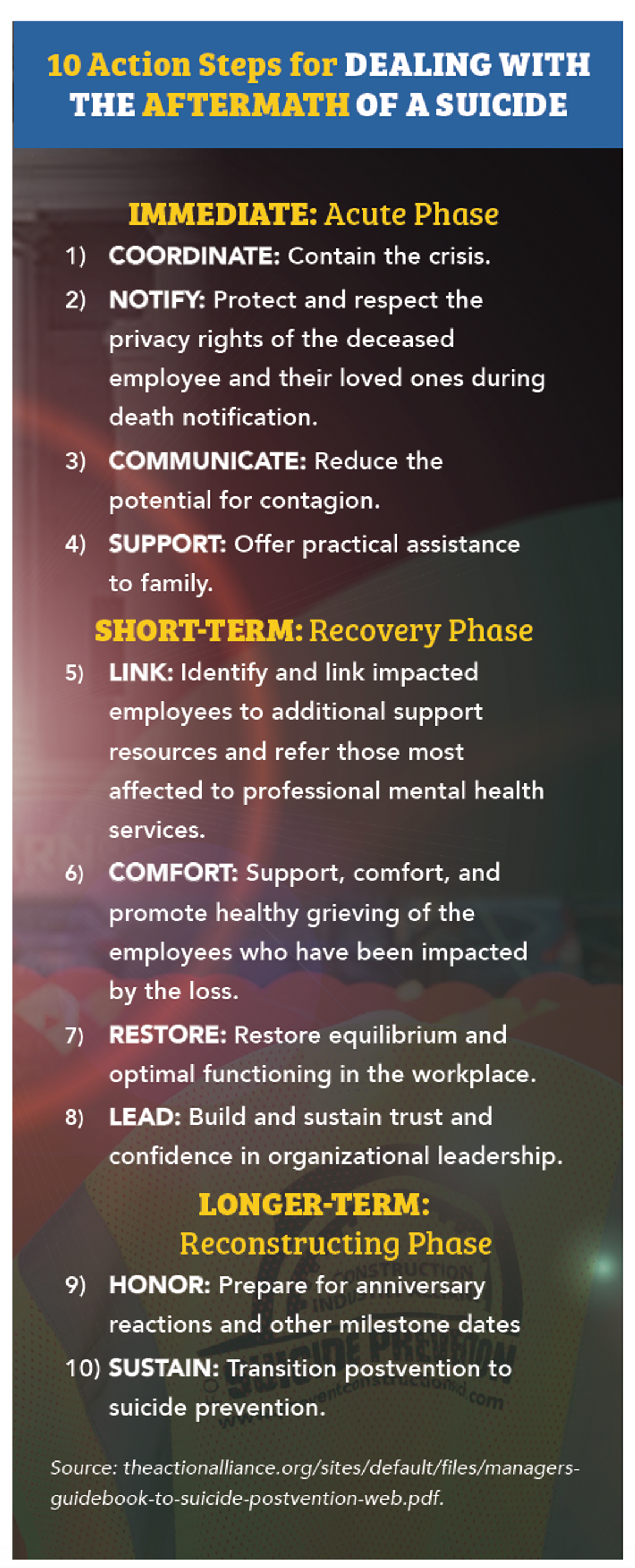

The objective of suicide postvention is to foster resilience – a return to productivity and a return to life – within the context of this new normal. Actions to take include:

- Coordinate to contain the crisis. Visible, strong leadership produces a contagious calm that mitigates the likelihood that one crisis will lead to additional crises. The impact of traumatic events often leads people to impulsively react in ways that cause further damage. Examples include hostile blaming at work or home, quitting one’s job, excessive alcohol use while driving, or high-risk behaviors including self-harm.

- Notify all stakeholders in a way that directly demonstrates both competence and compassion.

- Protect and respect the privacy rights of the deceased employee and their loved ones.

- Communicate pertinent information to internal and external stakeholders (e.g., employees, customers, subcontractors, media) to reduce the potential for contagion and destructive rumors.

- Support the family and others impacted by providing practical assistance (e.g., scholarships for the children;ma meal train; lawn cutting and landscaping; grocerymshopping; transportation; help wading throughminsurance issues).

- Connect employees who are impacted to information, informal support, and professional support.

- Comfort and support those impacted and promote healthy grieving. Recognize and communicate thatmthere is no one right way to grieve.

- Restore equilibrium by sensitively resuming a familiar schedule and familiar tasks. Even when those tasks are temporarily adapted, the focus on having some control reduces the feelings of powerlessness about the death.

- Lead visibly to send the message that leadership is capable of dealing with difficult challenges in a strong way that displays care for employees.

- Transition postvention into suicide prevention education.

After a death by suicide, those who are emotionally fragile can be at a greater risk of self-harm. Effective suicide postvention serves to prevent additional tragedies. Behavioral health professionals are skilled at assessing this type of risk and can triage to additional care accordingly.

Critical Incident Management (Including Group Debriefing Huddles)

If your company does not have a critical incident management process, this is a good place to start your postvention work. Critical incidents in the workplace, such as a suicide, can create a lot of pain, anxiety, stress, and guilt that can affect the mental health and well-being of workers.

Sometimes these critical incidents trigger unhealthy behaviors including, but not limited to:

- Increased alcohol use (self-medication) and binge drinking

- Anger and aggression, or even violent outbursts

- Anxiety and worry leading to distractedness, which can create safety risks

- Sadness and depression

- Self-harm and even suicide ideations or suicide attempts

It is important to acknowledge the suicide (or the triggering incident) and talk openly and honestly about the consequences of the incident, while making sure to not dwell on what happened, how it felt, or what people saw. It is also important to recognize that this is a leadership opportunity to start the recovery and healing process for everyone affected by the incident; this is the start of creating a “new normal.”

It is also an opportunity to bring understanding of how grief affects the individual, and how your people can take care of themselves and others during this time of increased stress.

In times of crisis, employees look to leadership to help them find a path to overcoming the stress and trauma of a critical incident. The critical incident debriefing is a purposeful safety huddle to provide a path toward getting help, providing hope, and for starting the recovery process. This promotes psychological safety in the workplace and reinforces resiliency among individuals and the group.

Strategies to Boost Resiliency & Counter Grief Following a Suicide or Another Critical Incident

- Drink plenty of water to stay hydrated and flush excess stress (“fight or flight”) hormones from your body.

- Avoid alcohol and sugary energy drinks.

- Stay connected and socialize. Do not isolate yourself.

- Eat – even if you’re not hungry. Staying nourished will help promote better rest.

- Try to maintain a normal sleep pattern. Take power naps as needed.

- Maintain physical activity and exercise patterns. Being physically active is good for your mental well-being.

- If needed, access help from your company’s EAP or behavioral health services (part of your health insurance benefits).

Q&A with the Authors

Bob VandePol and Cal Beyer first met near the Ground Zero Site in New York City after 9-11, where Bob provided critical incident debriefing services for contractors and first responders and Cal offered support to coworkers, business partners, and contractors. They started collaborating in 2005 when Cal was working with Arch Insurance and developing claim rapid response protocols.

Since then, they have collaborated on various media (including presentations, webinars, and articles in safety, construction, and insurance/risk management publications) and have both served on the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention’s Workplace Task Force. After being trained and coached by Bob, Cal has been a catalyst for suicide prevention efforts throughout the construction industry. Here, they answer questions surrounding suicide postvention.

Does talking about suicide make it more likely to happen?

Bob: Absolutely not. However, the way in which suicide is talked about can decrease or increase risk, especially among teens. Research indicates that when the topic of suicide is discussed in a non-sensationalized manner (that is, it does not glorify the deceased’s act or manifesto but rather defines it oftentimes as an extreme symptom of depression), then it can reduce risk.

Talking about suicide should include messages that encourage seeking help and should clearly point out where that help is available. A culture that defines suicide as a safety risk reduces shame and makes people more likely to ask for the help they need.

Cal: Another aspect to this question that cannot be overstated is how important it is for a person to be asked if they are considering self-harm or even killing themselves when they are distressed or showing warning signs of suicide. Asking this direct question can be the difference between life and death. By asking “Are you thinking about suicide?” you are showing the distressed person that you notice them, that they matter to you, and that you care enough about them to ask an awkward question that many would shy away from asking.

Why does suicide seem to be so much more shocking to people than death by other causes?

Bob: It goes against everything we are taught and everything we do to take care of ourselves. Death by suicide brazenly challenges all of the shared beliefs and efforts that support safety, growth, and success.

The million-dollar question is why do people die by suicide? Most of the time, suicide requires a multitude of contributing factors, but when impacted by this level of shock people attempt to immediately grasp onto one reason why someone could possibly do something so harmful. How they assign that blame to themselves or others can contribute even more pain.

Many suicidal people suffer from depression, with suicide being its most severe symptom. Our society still wrestles with the fact that mental illness is an actual illness. We are saddened and grieve deeply when someone dies from a medical disease, but still find mental illness perplexing.

Suicide also feels very personal, as others often think “How could this person do this to their family? Friends? Me?”

Cal: It is hard to comprehend the depths of pain, desperation, and despair that someone must be feeling to take their own life. When faced with a death by suicide, many loved ones are racked by guilt and shame. Much of this is symptomatic of the stigma around mental health and suicide.

Bob speaks of the sadness and futility when family members and coworkers try to determine who is at fault for a death by suicide. It is the unthinkable and we all have a hard time wrapping our brains around the permanence of the act.

What tips do you have for business leaders if they have to communicate a coworker’s death by suicide to employees?

Bob: First and foremost, honor the wishes of the family and ask them what they would like to have communicated. Sometimes they will want the cause of death to be made public for suicide prevention purposes; other times, focus on grief and healing rather than explicit details related to the cause of death. For example, language such as “Out of respect for the family who has lost so much, we choose to focus on our loss rather than cause of death” is usually received well.

Don’t fearfully avoid the issue, but rather compassionately with strength state the decision to focus on grief. Most coworkers will put themselves in the place of the grieving family and honor that decision. Business leaders will “go on record” as being respectful of those most impacted.

Cal: Listen and empathize. Provide concern, care, and comfort. Let them know that you’re there for them and ask them what you can do to help. Focus on hope, help, and recovery, along with ways to find a “new normal.”

Let them know that contacting the family to express condolences is generally appreciated, as many people will usually shy away because of the stigma around suicide. Sending a card and attending the memorial/wake is generally appreciated as well.

Also, remember that language matters. Instead of saying someone “committed suicide,” use the phrase “died by suicide” to reduce the stigma, make it easier to talk about, and remove blame from the person who died. After all, we don’t say someone committed a brain tumor or cancer. We must treat mental health like we do physical health to increase understanding, reduce stigma, and create empathy.

It is healthy to talk about the person who died and the bravery of enduring the struggle. It humanizes the victim and shows others (especially family and coworkers) that there is empathy and compassion during these moments of struggle.

If an EAP crisis consultant comes onsite, what should be expected of them?

Bob: They should respond as an invited expert who holds important knowledge that needs to be integrated into a company’s unique culture, schedules, and business objectives. An effective crisis consultant should:

- Consult with leadership to structure responses to what individuals and groups need most.

- Position leadership favorably through shared messaging. An external perspective can be very helpful while carefully preparing e-mails, scripts, and talking points.

- Allow people to talk, if they wish, without further stripping defenses.

- Identify and normalize acute traumatic stress reactions (e.g., difficulty sleeping; inability to concentrate; hypervigilance regarding suicide risk of other loved ones; rekindled grief from prior losses; high anxiety triggered by places; tasks, and memories related to the deceased colleague) so that those impacted by them do not become overly concerned about them.

- Build group support within work teams.

- Outline self-help recovery strategies.

- Brainstorm solutions to overcome immediate return-to-work and return-to-life obstacles.

- Triage movement toward either immediate business-as-usual functioning or additional care.

- Share themes and recommendations with leadership regarding next steps.

Cal: I agree with what Bob has outlined (and personally deployed). I would just mention that all crisis consultants and EAPs should be professional and compassionate.

What advice do you have for friends or family members of someone who dies by suicide, especially those who want to jump in and help others in the cause of suicide prevention?

Bob: Family members are uniquely qualified and sometimes uniquely disqualified. They should become involved under the guidance and feedback of a professional as well as their peers to ensure they will not be harming themselves or others by getting involved too soon.

Cal: Family members should be encouraged to take care of themselves by taking time to grieve, mourn, and process their feelings. This is exhausting work, especially when grief is so fresh. Many professionals caution against doing too much too fast. People warn of needing to experience major milestone dates (i.e., birthdays, holidays, anniversaries) before jumping in too quickly. They should find key people with whom to share reactions and responses to this work.

Partnering with professionals and associations is a way of getting engaged without having to do all of the “heavy lifting” to stay refreshed. Being a catalyst and getting others engaged is a way to reduce the burnout potential. Recharge physical, emotional, and spiritual batteries when they are depleted. It is okay to say no without feeling guilty. Timing is everything and you will know when you are ready to share your story, fund raise, or volunteer.

What should a business leader or coworker do if they are concerned about someone’s suicide risk?

Bob: Ask! It takes a lot of courage to ask this uncomfortable question.

Imagine if you were wrestling with suicide intentions and felt as though you were sending out risk signals, but nobody seemed to notice. Language such as “I care about you enough to risk ticking you off. I have seen and heard some things that concern me. Are you thinking about killing yourself?” should be used nonjudgmentally to initiate the conversation.

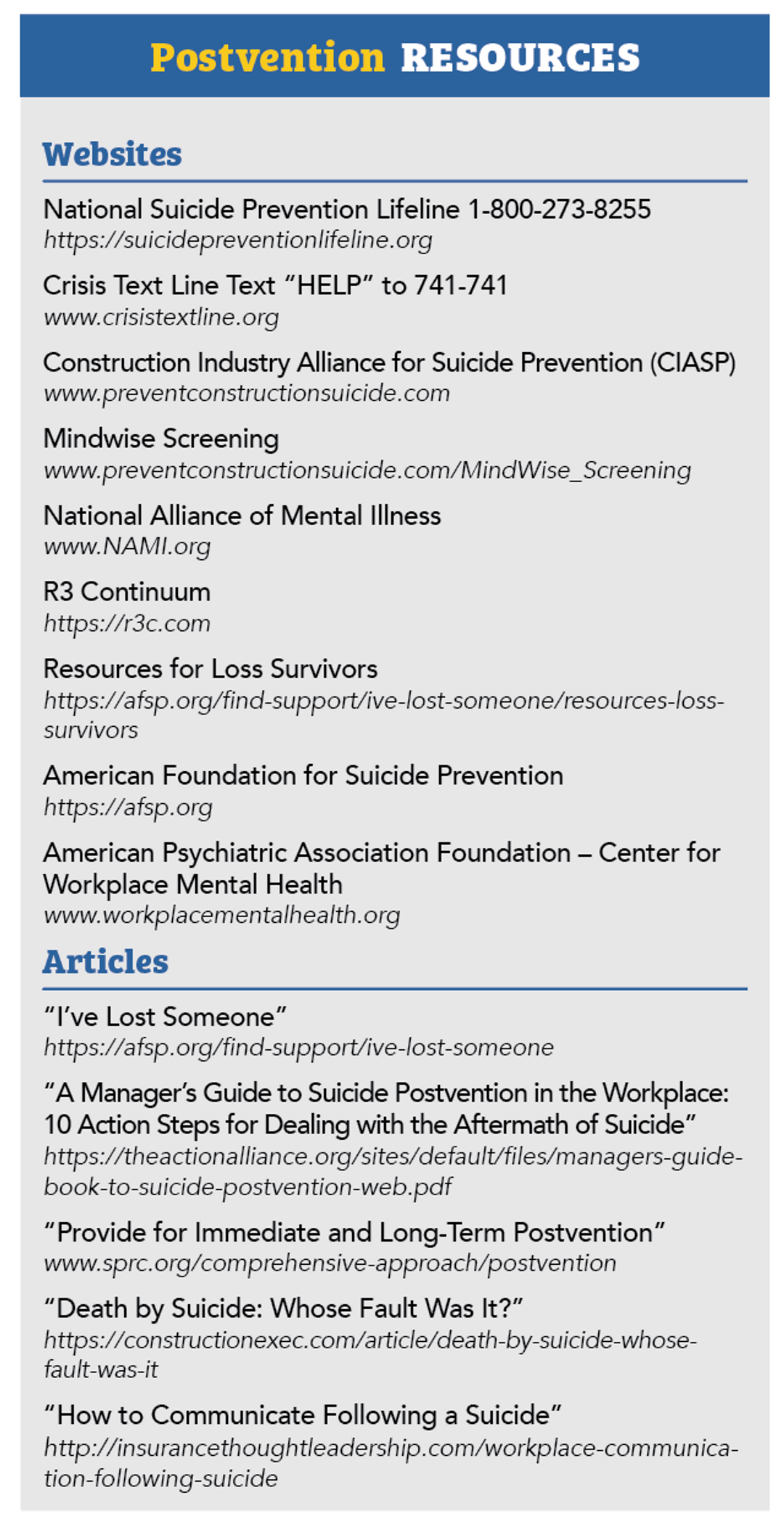

Cal: Take immediate action. Let the affected individual know that you care and that you are willing and able to offer them resources. There are many different resources (see page 30) from which one can learn how to safely have these conversations. Offering to help them call one of the crisis hotlines or the EAP is another way of showing you support them. Regularly check in with the person to see how they are doing and to remind them that you are still there for them day or night.

What is the most rewarding aspect of your suicide prevention and postvention work?

Bob: When I look into someone’s eyes and see:

- Someone who successfully made it past a suicidal crisis and is now thinking, “Wow. How was I ever in that dark place? I’m gratefully taking care of myself to make sure I never go there again.”

- A business leader or coworker who helped a colleague through that crisis and witnessed their return to a healthy life and work.

- A family member (of those) whose loved one is now back to being themselves.

- An exhausted business leader who knows they led their team competently and compassionately after a death by suicide.

- A suicide prevention champion who brings passion and expertise of saving lives into the corporate setting.

Cal: Being able to make a difference in the lives of others is a motivation for many safety, risk management, and human resource professionals. It is rewarding to offer support and resources to help a person through challenging circumstances and have them get help for themselves or a loved one. I have felt no higher calling than my work in suicide prevention. It is the most meaningful work I have ever experienced.

Copyright © 2019 by the Construction Financial Management Association (CFMA). All rights reserved. This article first appeared in November/December 2019 CFMA Building Profits magazine.