Whether it’s a fluctuating economy, an evolving style trend, or a shifting mindset, the architecture, engineering, and construction (A/E/C) community responds and adapts to change without delay.

Now, this community is leading a transformative movement for the wellbeing of large workforces and communities.

Promoting Physical & Mental Wellbeing Through Design

One of the most significant and enduring “silver linings” resulting from COVID-19 may be that mental health and wellbeing have become top of mind for many companies and industries. However, even before COVID-19, a subtle yet significant shift to promote physical and mental wellbeing was already underway in the global real estate development market.

What is this shift? Owners and developers are increasingly incorporating and designing features into the built environment where people live, work, and play. A major impetus for this shift in momentum is the increasing amount of time people spend inside buildings, which is now estimated to be approximately 90%.1

Examples of design features that promote wellbeing include, but are not limited to:

- Increased natural lighting and decreased glare

- Enhancements to fresh air ventilation and exhaust

- Larger windows to provide clear views

- Open stairwells to encourage walking

- Features to enhance safety (such as interior and exterior motion activated lighting fixtures) and equity (such as multi-lingual informational signage)

- Indoor and outdoor break rooms, including open-air patios or rooftops

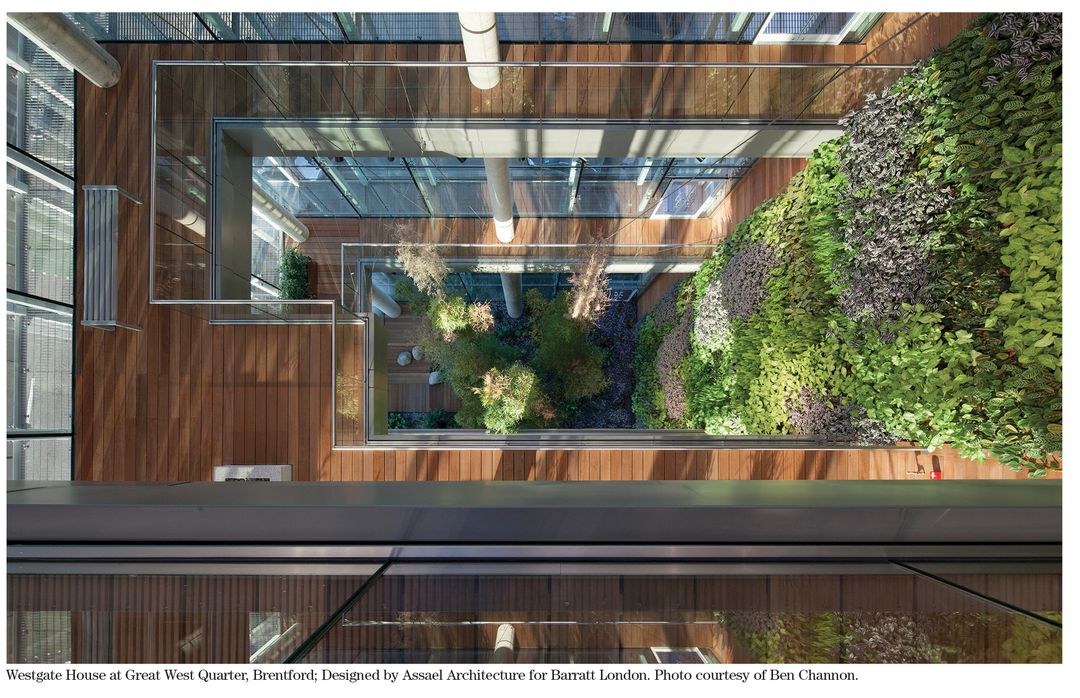

- Biophilia,2 waterfall structures, and other forms of bringing nature indoors

- Adjoining or adjacent exercise areas, including walking trails and pet parks

- Access to healthy food in a building or local community complex

- Integrating mass transportation, carpooling, or bicycle sharing for employees

There are many factors driving this focus on wellbeing in the built environment (see sidebar below), with measurable impacts of this shift creating new demand across markets. For example, focusing on design elements of commercial office spaces – like attracting and retaining tenants or employees – can have a profound impact.

Also, as reported in the health care section of The Des Moines Register, a project found that increasing window square footage in a pediatric hospital showed a 15% improvement in a patient’s ability to manage pain and a 25% improved rapid response to care.3

Moreover, the impact is also seen with individuals when buying homes. According to the International Well Building Institute (IWBI), 60% of homeowners are willing to pay more for a home “that could be demonstrated to have positive impacts on occupant health.”4

Cost vs. Return on Investment

When innovative thinking or changes in the status quo are challenged, one of the first practical hurdles to overcome is the increased investment it may take to embrace and adopt this new way of thinking. Although still important, the focus of this article is not the expected return on investment (ROI) and added costs of this shift, but rather the potential improvement of physical and mental wellbeing.

The IWBI states that design elements that bolster wellbeing in a project may roughly run 1-2% of a proposed budget, while experts in the field note it can range slightly higher at approximately 1-3%. Instead of considering the cost to implement these changes, it is worth considering the opportunity costs if you fail to make these investments.

Examples of potential paybacks to consider when evaluating the investment in wellbeing could include:

- Being an employer of choice with a highly desirable space to help recruit and retain high-performing talent.

- Helping tenants reduce high turnover rates inindustries by providing convenient, accessible workplaces with desirable design features.

- Freeing capital for new investments by selling out a development faster.

- Renting or leasing at premium prices or securing longer-term leases to maximize investment returns.

- Enhancing reputation and community goodwill by addressing inequities by improving accessibility and/or inclusion.

Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED®) arguably raised the sustainability floor in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Two certification programs, the WELL Building Standard and the Fitwel Certification Standard, aim to have their standards similarly raise the floor for attaining wellbeing in the built environment while impacting public health.

Case Studies in Wellbeing Design

To highlight the importance of wellbeing design, here are some real-life examples of the approaches taken by two firms to meet the emerging needs of project owners. They illustrate the impact and benefit of wellbeing innovative designs beyond the ROI.

Senior Living Communities – RDG Planning & Design

Jay Weingarten, AIA, WELL AP, is an Architect with RDG Planning and Design – an architecture firm with locations in Des Moines, IA, St. Louis, MO, and Omaha, NE. When he approaches each project, he not only focuses on the aesthetics, but also the intentional selection of materials and design elements that positively impact the mental and physical wellbeing of the end user.

Weingarten found it disappointing that there was no formal training in architecture school on how to design spaces to improve mental and physical health, but a clear majority of what can determine our health outcomes is driven by the space we live in. “It just wasn’t something that people were thinking about yet when I was in school,” he said, “but I am passionate about health and wellbeing and want to find a way to incorporate it into our work.”

Weingarten looked to the WELL Building Standard to incorporate research-based design elements in the short-term rehab skilled nursing environment, as these elements have been proven to have a positive impact on the residents and staff. The team developed strategies to raise the bar for things like indoor air and water quality, which are common in the industry, but also dug into less common nuances like the impact of paint colors and ceiling heights on the perception of light within a space.

RDG, with the assistance of WELL coaches, spent time researching the impact that light had on an individual’s wellbeing. For a skilled nursing facility, residents are not only there to recover, but often stay for many days. RDG incorporated innovative features like passive circadian light design, the balance of natural and artificial light in a room, and the visual temperature of paints to create a more marketable end product.

As a result, RDG successfully completed the first skilled nursing building in the world to be WELL certified, having achieved Gold certification. Weingarten knew that the strategies the team had chosen to implement during the design process were successful when a resident mentioned during a post-occupancy evaluation that the quality of light was amazing and brings encouragement. The resident stated, “I woke up to natural light in my room and could see everything, and went a whole morning without realizing I hadn’t turned the lights on.”

Behavioral Health Projects – Pope Architects

According to Erica Larson, CID, CHID, EDAC, LEED AP BD+C, and Principal with Pope Architects based in St. Paul, MN, a rapidly growing design trend for employee wellness is one of the primary drivers and project goals for Pope Architects’ clients. Openly discussing employees’ physical and mental wellbeing in the workplace has become more acceptable.

“Our clients are seeking out holistic and innovative measures to incorporate key concepts within their physical environments,” she noted.

Larson affirmed that ROI has not been the primary motivation for clients and owners in selecting wellbeing design for the built environment. She echoed that the “attraction and retention of employees is what we are seeing in the discussions surrounding employee wellness in the workplace.” She noted that it is consistent with the growing mindset of human capital risk management in which “employees are an organization’s greatest asset and cost, and now more than ever our clients are designing their workplaces for their people.”

Larson described how the health care team at Pope Architects is “addressing behavioral health needs within the workplace by designing more varied space types that allow employees to choose how and where they work best based on the task and/or their mindset.”

She noted that the team also focuses on “designing to balance spaces such as enclaves or quiet rooms for heads-down work, contrasting with an increase in communal and collaborative spaces for socialization and human connection.”

Other examples of these areas Larson referenced as being of “extreme importance included wellness rooms, game rooms, prayer rooms, and outdoor spaces.”

Larson shared both professional and personal perspectives on why she believes designing for wellbeing is now being emphasized. “Behavioral and mental health has affected so many people, touching all of us in different ways. Family members, friends, and colleagues have struggled with a multitude of substance abuse and mental health issues throughout my life. Personally, I battle the need for perfection in all aspects of my life, which inflicts heightened pressure, stress, and anxiety. As a result, doing my part to help reduce the stigma surrounding behavioral and mental health is of utmost importance to me.”

Larson’s perspectives are examples of “lived experiences,” which are powerful first-hand testimonies in reducing the stigma associated with mental health. These stories further increase the ease with which people talk openly about mental wellbeing.

Conclusion

The A/E/C and real estate industries are leading a transformative social and economic movement involving both practical and innovative design strategies. This development has the potential to significantly impact the physical and mental wellbeing in various built environments. Wellbeing design strategies have broad applications in numerous sectors and types of occupancies, and can benefit both high-risk populations and societies at large.

Designing for wellbeing is another area where the construction industry can do well by doing good – being profitable while simultaneously addressing a sustainable future by investing in projects and portfolios focused on meeting reasonable environmental, social, and governance objectives.

Endnotes

- Allen, Joseph G. & Macomber, John D. “Healthy Buildings: How Indoor Spaces Drive Performance and Productivity.” Harvard University Press. 2020.

- Biophilia is a hypothetical human tendency to interact or be closely associated with other forms of life in nature; a desire or tendency to commune with nature.

- Householder, Tonia. “Architecture concepts can boost mental health.” The Des Moines Register. April 22, 2016. www.desmoinesregister.com/story/opinion/abetteriowa/2016/04/22/architecture-concepts-can-boost-mental-health/83341812.

- “The Drive Toward Healthier Buildings: The Market Drivers and Impact of Building Design and Construction on Occupant Health, Well-Being, and Productivity.” McGraw Hill Construction. 2014. www.worldgbc.org/sites/default/file/Drive_Toward_Healthier_Buildings_SMR_2014.pdf.

Copyright © 2020 by the Construction Financial Management Association (CFMA). All rights reserved. This article first appeared in November/December 2020 CFMA Building Profits magazine.